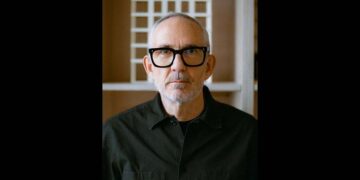

at the Künstlerhaus, Vienna.

The Silent Dialogue: An Interview with Seung H-Sang at the Künstlerhaus, Vienna

The exhibition hall was filled with an aesthetic of emptiness and restraint. At its heart stood a pure white installation titled ‘Dokrakdang’—a sanctuary of stillness where the numerous ‘words’ the architect has drawn from the land, the era, and human life over a lifetime seemed to condense.

At the Künstlerhaus in the heart of Vienna, Seung H-Sang appeared both humble and resolute. More than 40 years ago, this city served as a refuge for a wandering young architect; now, he has returned as a master to reaffirm his architectural origins. In a modest space on one side of the exhibition, Herbert Wright sat down with Seung.

Beginning with the opening verse of the Gospel of John and spanning to the anxieties of the AI era, their conversation, accompanied by the warmth of a cup of tea, unfolded as a record of the intellectual struggle hidden behind the act of building.

→ Read: Seung H-Sang Exhibition in Vienna, ‘Architecture and Words’

Herbert Wright: You introduce this exhibition with a projection that says, “In the beginning was the Word.” Why did you choose this quote from the Gospel according to John?

Seung H-Sang: I consider myself a good Christian, but religion is slightly separate from this exhibition. I became an independent architect in 1989, after working for 15 years with Kim Swoo-geun, who is often called the father of Korean modern architecture. He passed away in 1986, very young, at the age of 55. He was a truly great man, and I learned architecture from him.

After he died, I worked for three more years at SPACE Group, and then I established my own office, IROJE, in 1989. At that time, however, almost everything I knew about architecture came from Kim Swoo-geun. I had to find my own path. After several years of quite a fierce inner process, the words “beauty of poverty” came to me.

Herbert Wright: What are you saying with this expression, “beauty of poverty”?

Seung H-Sang: When I was walking around a small village in Seoul, I found it very moving. We call it a “moon village” – a hillside settlement where poorer people live.

Herbert Wright: A mountain area in the middle of the city?

Seung H-Sang: Yes. Walking along the narrow inner streets, I was reminded of my hometown in Busan, of my youth in a village of North Korean refugees. My parents came from the North. The spaces, the structures, the debris – they were all very similar to the moon village. I felt very familiar with it.

I realised that the spatial structure there was very interesting. The houses and plots are usually very small, but people share a common life on the street. The street is not only a way to walk and pass by. They live there; they gather, play, and talk there.

Herbert Wright: There is a sense of community, and it makes the communal space come alive.

Seung H-Sang: Exactly. The life of the poor is very beautiful – that realisation came to me. That is when I found the words “beauty of poverty”. With that phrase, I felt I could do architecture in a way that was different from others.

Since then, I have concentrated on those words, but a single phrase is only a kind of declaration. I needed more words to think through my architecture – words like emptiness, or function, or silence, or city, which in different ways all follow from poverty. I needed more and more words. This is why I emphasise the relationship between words and architecture.

Herbert Wright: You speak of the “beauty of poverty” and of people such as the refugees in moon villages. This seems very different from much of your work, which is about solitude and tranquility. On the one hand there is this lively communal life and its architecture, and on the other, architecture for contemplation and being by yourself in an inner space.

Seung H-Sang: At first, I wrote down four principles that define “pure poverty”. They are set out in this book. There are four components. The first is space – space as emptiness. The second is function. The third is form. The last is the relationship with the city.

For more than 30 years, I have practiced architecture based on this idea of the beauty of poverty. During that process, I discovered two more components: one is memory, the other is soul, or spirit.

I have worked not only as an architect in private practice, but also in the public sphere, as the first City Architect of Seoul. During that period, from 2014 to 2016, I realised that Seoul is a kind of “soul-scape”. The landscape of the soul is extremely important for Korean society – and not only for Korea, but for the world.

Today, Korean society is one of the most dangerous in the world in a psychological sense. The suicide rate is the highest among OECD countries. Roughly every 38 minutes, one person takes their own life. It is a very dangerous society, partly because people lose their families, their positions, their sense of place. Nowadays, younger people suffer even more than older people.

Economically, Korea is very wealthy. Our GDP is among the highest in the world. But the society is very unbalanced. I studied why this is so, and I concluded that a loss of spirituality is one of the most fundamental reasons. So I wanted to reinforce a kind of “soul-scape” in the minds of Korean people. Over the past ten to fifteen years, I have focused on these concepts in my architecture.

Herbert Wright: This idea of “In the beginning was the Word” is a quote from St John. The Beatles have a song called The Word, where “the word” is love. But what worries me is the parallel between God and the architect, and the experience of some architects who seem to feel like God – like Le Corbusier with his social housing plans. That can lead in the wrong direction, can’t it?

Seung H-Sang: No, I don’t think in that way. The architect does not design his own house. He or she designs for the lives of others. That is a very delicate and precious task. In that sense it is a little bit like God – but God does not fail. Architects can fail.

Herbert Wright: Exactly – architects can fail. Is it not dangerous for an architect to imagine having a God-like power to create worlds in which people must live?

Seung H-Sang: An architect must always be careful about that. I am always anxious about the architecture I design. If you look at my sketches, the lines are never very straight; they are timid. I cannot draw boldly. I cannot be proud of my ability. I am always afraid of damaging other people’s lives, so I pray to God to give me some ability.

I think all the architecture I have designed is, in a way, a mighty record of failures. At the same time, this becomes a motive for me to keep designing, and to do better in the future.

Herbert Wright: Would you say there are particular projects of yours that you regard as failures?

Seung H-Sang: All of them.

Herbert Wright: Because you don’t feel they are perfect?

Seung H-Sang: Not only that. There are many reasons. Architecture must always be done with others – with clients, with my staff, with contractors, with other collaborators. Architecture is never completed by myself alone. You have to collaborate with all these people. So during design and construction, there are many possible sources of failure.

The difference with an artist is that an artist can work alone in a dark room. When the work is finished, they can show it. Architectural work cannot be done in that way.

Herbert Wright: I think many artists also fail, because they have to compromise with an art world driven by money – but that is another subject. Let me ask about Vienna. How does it feel to be back after all these years, and what has your experience been with visitors to the exhibition here?

Seung H-Sang: I first came to Vienna in 1980. At that time, the political situation in Korea was very difficult because of the military dictatorship. In May 1980, during the Gwangju Uprising, so many people were killed by the army.

Because of this, I felt frightened for my life and my future. Just then, I had finished an architectural project whose client was Austrian – a priest from Graz. We became very close friends. He advised me to come to Vienna. He arranged my admission to TU Wien and even accommodation in a monastery. He was a very good man. So I studied at the university, and I got married here. I had many friends and many kinds of kindness from Vienna.

I lived here only for two years, then returned to Korea because my teacher Kim Swoo-geun asked me to work with him. Korea had been selected to host the Olympic Games, and many architectural projects were needed. I went back and worked with him for some years. Since then, I have felt that Vienna could be my second hometown.

Later, TU Wien invited me as a guest professor in 2017, and in 2019 the Austrian government awarded me the Cross of Honour for Science and Art, First Class. So I am deeply connected with Vienna.

Herbert Wright: What do you think of the great Viennese architect Friedensreich Hundertwasser? I sense some parallels with you, in terms of spirituality and a deep philosophy.

Seung H-Sang: Yes, he articulated a philosophy. At one time, I thought an architect could simply be a kind of artist, but I realised that this is not true. An architect cannot only be an artist. An architect must be an intellectual, someone who can say something about the times, about our life. So the text, the thinking behind the work, must be intellectual. Once I understood that, I had to rewrite my own thinking about architecture.

Hundertwasser chose solitude because he always worked in discord with the world. That element of solitude also became part of my life. I think he was a great artist, but I find it difficult to regard him fully as an architect. As far as I know, he did not really propose different ways of living or new forms of community. I have seen several of his works. Usually he designed very beautiful, wonderful façades and forms, but I could not find any real revolution in the life inside.

Herbert Wright: Of course an architect can be an artist at the same time, but you are saying that Hundertwasser was mainly making stylistic architectural changes, rather than changing what happens in the building. How many architects actually propose something different about the life inside a building? Someone like you can create a wonderful place to meditate – and there are examples here in the exhibition. Is that what separates you from Hundertwasser?

Seung H-Sang: I believe he was devoted to people, especially through his social housing, such as the Hundertwasserhaus of 1985. But when I think of architects who are truly revolutionary, I would name Louis Kahn or Mies van der Rohe.

Herbert Wright: Coming back to Vienna today, has the city changed? And how are visitors to the exhibition interacting with you?

Seung H-Sang: Vienna has the same basic character, but it has become richer and more crowded. There are so many people, so many tourists. Even in the subway I was surprised.

Herbert Wright: Couldn’t you say the same about Seoul?

Seung H-Sang: Yes, and that brings many problems. But here in the exhibition, I see something different. As people enter the space, they become very careful and calm. They are very curious to see what is there.

Herbert Wright: The exhibition – and meeting you – is wonderful. It slows people down, makes them more tranquil. The same is true of your architecture.

Seung H-Sang: I hope so. That is the goal of this exhibition. It consists of four parts. One is the projected texts on the wall, which express my position in the world. The second is the tables with sketches and photos – sixteen projects from the world. Then there is the installation of this small house. And finally there is the empty space between the works around the walls and the small house. In that empty space stands a single chair that I designed. Its name is the Monk’s Chair.

Herbert Wright: I really enjoyed going through your projects. Many are outside the city, but one urban project that enchanted me is Siudang (2017–2019), The House Where Poetry Rains, built for an actress living in a fast-changing part of Seoul. The building itself looks like poetry. Could you tell us about its design and features? For example, the spire that brings light into a 12-metre-high room, making beautiful patterns.

Seung H-Sang: The pattern is the constellation Aquarius. When the client came to see that space, she was very moved. She eventually confessed to me that this space must be her tomb, so I designed a kind of box for her. Afterwards she lived there, and every day she could look toward her own afterlife. In that way, she had to consider her life carefully. That was my intention.

Herbert Wright: So that was a house for her to live in, but also to die in – and to have her afterlife. I also loved looking at Cheomdan, Altar Ascending to the Stars (2018–2019), where an exterior stair leads to a view of the sky from above a hilltop. Just from the model, it reminded me of the beautiful arkhitektons that Kazimir Malevich made in the 1920s and 30s. Could you tell us about Cheomdan?

Seung H-Sang: Cheomdan is like a stairway to heaven. It is in the Sayuwon Arboretum, where I have designed several buildings over the years. Most of the architecture I designed there stays in the background or is hidden, because the trees are the first things you see. Cheomdan is actually a functioning water tank. To achieve the necessary water pressure, the structure has to rise above ground. It can be seen as a kind of altar to the stars, but inside it simply holds water.

Herbert Wright: Another vertical structure that struck me is Josa. Could you tell us about this ‘Monastery of the Birds’ – a narrow bamboo tower with five levels?

Seung H-Sang: The client asked me to design a bird nest. I studied the birds in that area. Many species fly at different heights – some like eagles, some near the ground, some on the water. I wanted to gather all those birds into one structure. At the same time, I thought it could be a vertical monastery. So the first level is a chapel, the next one is a library, then a dining room, a sleeping room, and so on. In my mind, it became a kind of small monastery for birds. The owner provides food there, so many birds come.

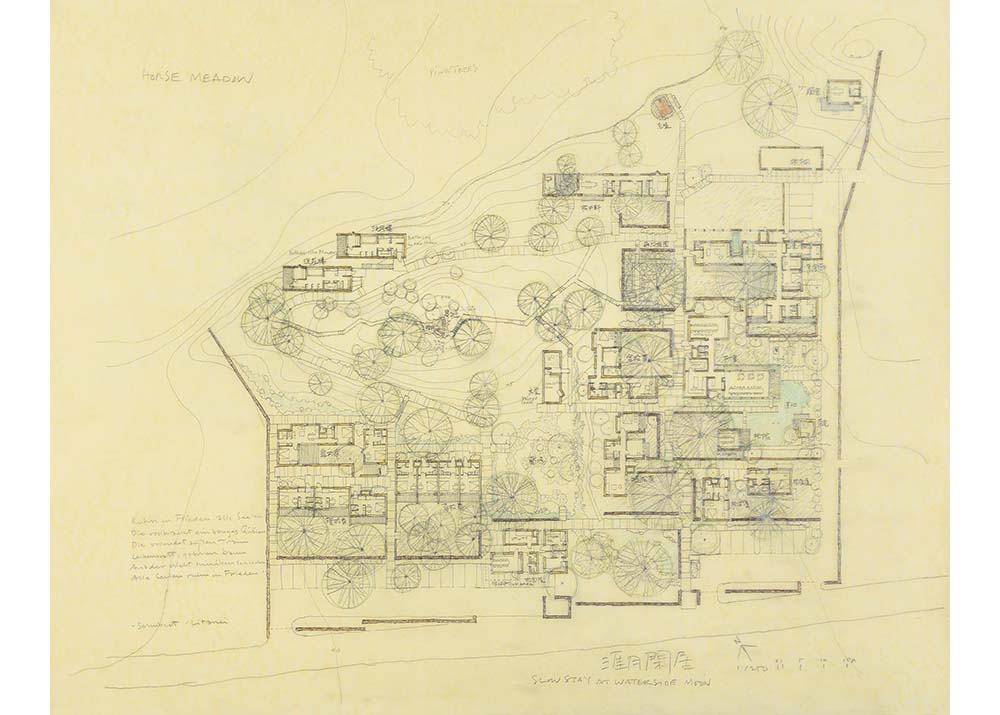

Herbert Wright: Could you tell us about Aewol Hangeo, Refuge of the Moon by the Water (2021–2025) on Jeju Island – a retreat among the trees? It seems like a village with water, and it has that sense of tranquillity we find throughout your work.

Seung H-Sang: That project was completed very recently, last May. Do you know Jeju Island? It is very beautiful because of its volcanic topography, with a mountain rising in the middle. At the same time, Jeju has a tragic history – colonised by the mainland, invaded by the Japanese military, and in modern times the site of uprisings and brutal suppression by the central government. Many people were killed in conflicts between left and right.

A client asked me to design accommodation there. On the site there are 45 pine trees, most of them two or three hundred years old, and very dense. I felt that the pine trees were the true owners of the land, so none of them could be harmed. I promised each pine tree that I would take care of it. I gave a territory to every tree, and in order to protect those territories, I surrounded some of them with buildings, fences or walls. The trees and the land told me what kind of architecture they wanted. I listened to what they said.

For cases like this, where the landscape carries stories, I use another word – “landscript”. If you search for it in Wikipedia, you will find that I introduced that term!

Herbert Wright: Let me ask about the future. First, will you carry on working, or do you feel the time has come to retire?

Seung H-Sang: I will carry on designing, and I hope I can do so without failure.

Herbert Wright: That is a very profound answer. My other question about the future is more general. There is a lot of anxiety – not only about climate change, inequality and so on, but also about artificial intelligence. In architectural practice, we already use AI within digital tools. What is your opinion?

Seung H-Sang: Yes, I know many architects now use AI as a tool. But one thing AI cannot do is worry. It cannot experience creative anxiety. AI is always confident.

I believe an architect must worry – about whether his or her work is right, whether the direction leads to good quality, whether it might harm someone’s life. This kind of anxiety can make the work better. I am always caught by anxiety, but it gives me energy to go on and to continue my work.