Talking Quietly of Powerful Words to Make Architecture

In the Künstlerhaus (Artist’s House), a handsome 1868 neo-Renaissance building in the heart of Vienna, Austria, Seung H-Sang had been coming every day at four o’clock to meet and talk with the public. The stage for these encounters was an exhibition about his architecture, called Architecture and Words, and it included 16 projects from this century. Seung had returned to the city he first came to in 1980, to live and study. Shortly before the show closed in November, Seung talked to C3 about his connection with Vienna, his philosophy and some of his recent works.

After graduating from Seoul National University and studying at TU Wien, Seung worked under Kim Swoo-guen, credited by many, including Seung, as ‘a father of modernity in Korean architecture’. Seung founded his own practice IROJE architects & Planners in 1989, which won acclaim for projects such as the ‘Youngdong Jeil Women’s Hospital’ (1992) and ‘Daehakro Culture & Art Center’ (1996), both in Seoul, and ‘Subaekdang’ (1999), a white concrete house in Namyangju-si, Gyeonggi-do. From 1992, he developed his architectural philosophy of ‘beauty of poverty’, against the prevailing trends engendered by capitalism and the materialist society it created. Instead, Seung advocated architecture for a simple life, with foundations in empty space (recalling the Korean traditional courtyard, the ‘madang’), function, and relationship to location with its spirit and accumulated memory.

‘Beauty of Poverty’ was published as a book in 1996, and updated in 2016. Nowadays, when Seung has lamented the ‘backward notion of architecture as real estate’, and economic success has driven social dysfunctions in Korean society, particularly the young, his ideas seem more relevant than ever. His book Soulscape (2024) reviews spirituality in his work, and the title word which he coined becomes a powerful assertion for spirituality as it is lost.

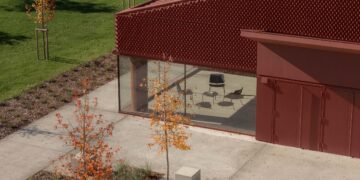

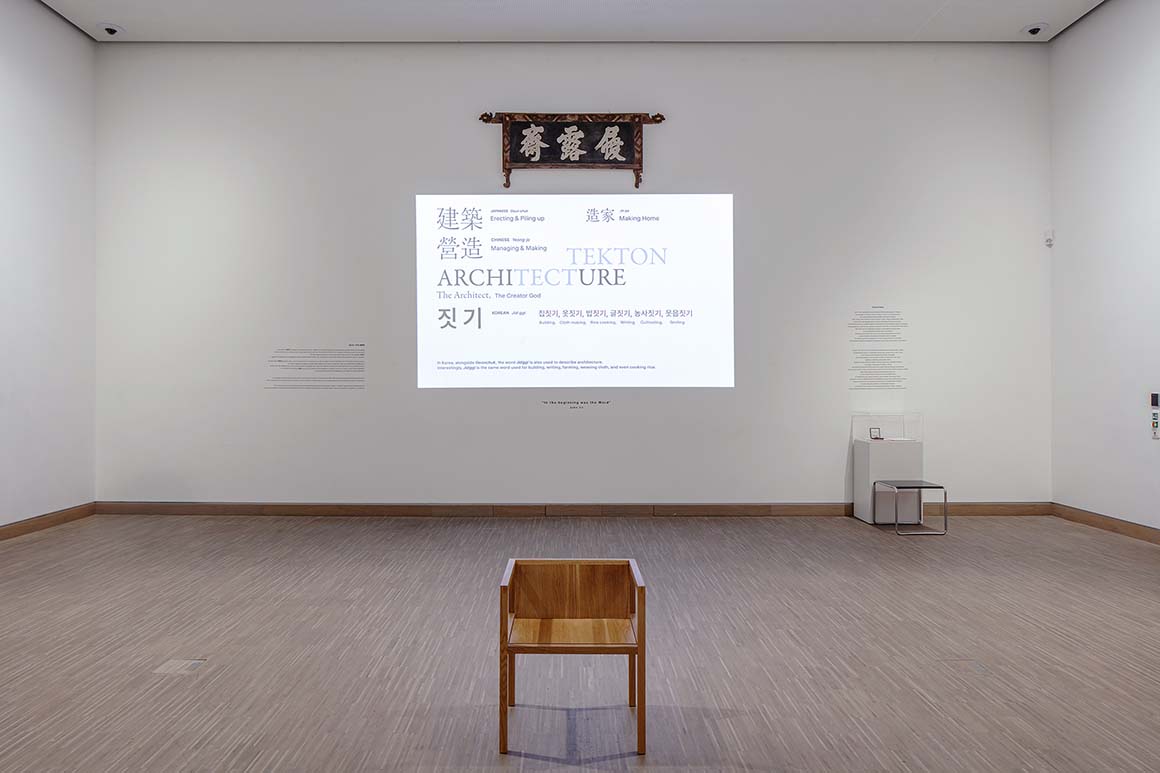

Seung was Seoul’s first City Architect (2014-16), and has taught and been honored with awards, both nationally and abroad. He could be described as a ‘Christian Brutalist Revivalist’, not just because he can design something like the ‘Dolmaru Catholic Church’ (1995) in Dangjin, the ‘Muhakro Methodist Church in Hayang’ (2018/C3#403) or others that stand with the very best of the typology when concrete and natural light are prime materials. Examples of Christian-related work recurred in the Vienna show, such as the major four-story concrete block of the ‘Retreat Center for Order of St. Benedict Waegwan Abbey’ (2024/C3#436) and ‘Myungrye Sacred Hill’ (2018/C3#422), a complex including a convent and a restored 1938 church on a hilltop site considered holy. Even the bamboo tower for birds, ‘Bugye Arboretum Sayuwon Birds’ Monastery’ (2013/C3#411), called ‘Josa’, has a chapel within it. Moreover, Seung says the show’s starting point was the line ‘in the beginning was the word’, from the Gospel according to St. John. Another projected slide referred to the architect as ‘creator god’, chiming with the word ‘tekton’ that is the root of ‘architect’ as well as the Greek description of Jesus as a maker. (Kazimir Malevich called his architectural conceptual models ‘arkhitektons).

Of course, there is much secular work in Seung’s output, as was seen in the exhibition. Examples include a magical house embedded in Seoul’s urban fabric, ‘Aquarius Pyramid’ (2021/C3#418) and the ‘President Roh Moo-hyun Graveyard and Memorial’ (2010/C3#422, 2022) which integrates into Roh’s home village and the landscape itself as ‘sentimental topography’. There are several projects away from the cities, such as those in the Bugye Arboretum ‘Sayuwon’ (2013-2024/C3#411) situated between mountains north of Daegu. Key to Seung’s design is a response to ‘landscript’, a word he coined that addresses the accumulated past embedded in the land. A sense of tranquility, peace and contemplation weaves disparate projects together, from the city to remote locations shaped by nature.

The Architecture and Words show had four spatial parts: a wall for projections, as mentioned; the 16 projects around three walls, with models, drawings, photos and descriptions on table-mounted wooden panels; an open space with a single chair of Seung’s design, and a small white installation enclosing a ‘moonbang’ (traditional Korean scholar’s room).

It was in the plain, ordered interior of this simple house-like installation that Seung served Korean tea as we talked, while Arvo Pärt’s minimalist, meditative composition Spiegel in Spiegel played, setting a mood that perfectly complemented Seung’s gentle manner, humility and humanist spirit. Text by Herbert Wright, C3 Editor-at-Large; Materials provided by IROJE; Photograph: JongOh Kim