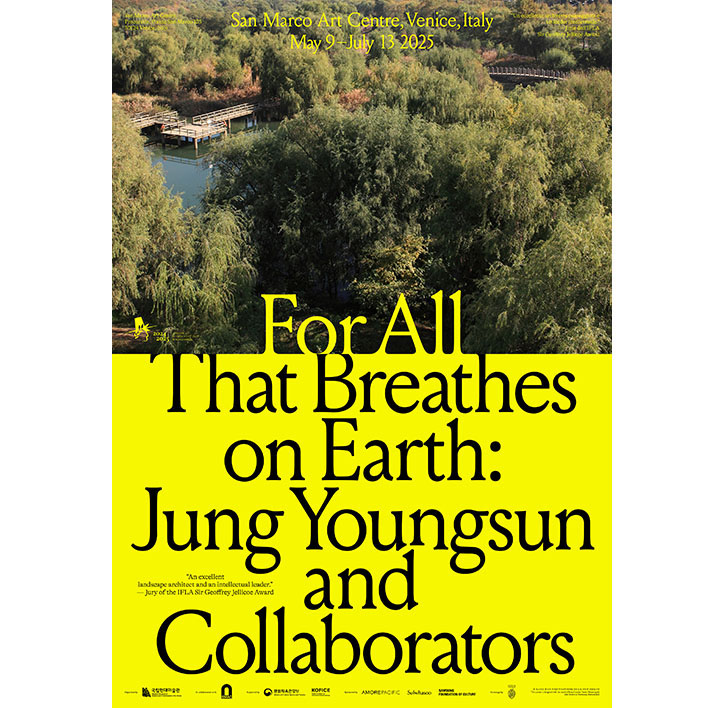

In May 2025, the work of pioneering Korean landscape architect Jung Youngsun (b. 1941) finds new expression in Venice. Titled For All That Breathes on Earth: Jung Youngsun and Collaborators, the exhibition has opened as the inaugural show at the newly founded San Marco Art Centre (SMAC). Running through July 13, the exhibition aligns with the opening weeks of the 19th Venice Architecture Biennale, marking a pivotal moment where the philosophy and aesthetics of Korean landscape architecture intersect with global urban discourse.

SMAC is located in the Procuratie, a 16th-century civic building at Piazza San Marco, reimagined as a new platform for visual culture. The renovation was led by David Chipperfield, the 2023 Pritzker Prize laureate, who also joins the exhibition as an official collaborator. His involvement draws on a longstanding partnership with Jung, first initiated through their collaboration on the Amorepacific Headquarters (2017) in Seoul.

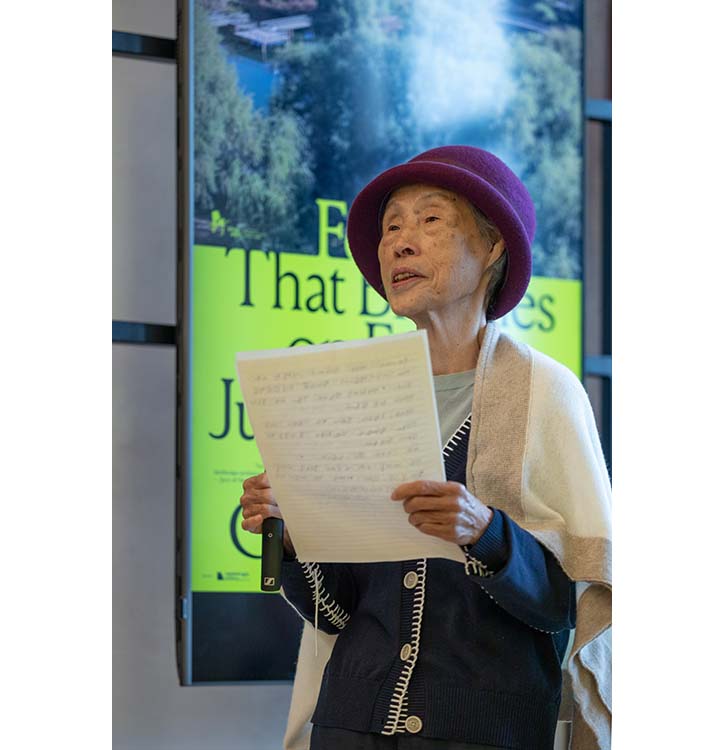

The opening ceremony, held on May 7, was attended by leading figures including Jung Youngsun, architects Min Suk Cho and David Chipperfield, the Korean Ambassador to Italy, the Deputy Mayor of Venice, the Vice Minister of Culture, Sports and Tourism of Korea, and Qatar’s Sheikha Al Mayassa. Chipperfield notably described Jung as “a national treasure of Korea,” offering tribute to her lifelong contributions to the field.

Jung has long practiced landscape architecture not as an act of imposition but as a language of dialogue. Her work consistently reflects the contemporary values of resilience and sustainability, emphasizing an ecological and site-specific approach to landscape design. This exhibition offers a condensed yet comprehensive view of her six-decade career and marks the first major European presentation of the conceptual and formal depth of Korean landscape architecture.

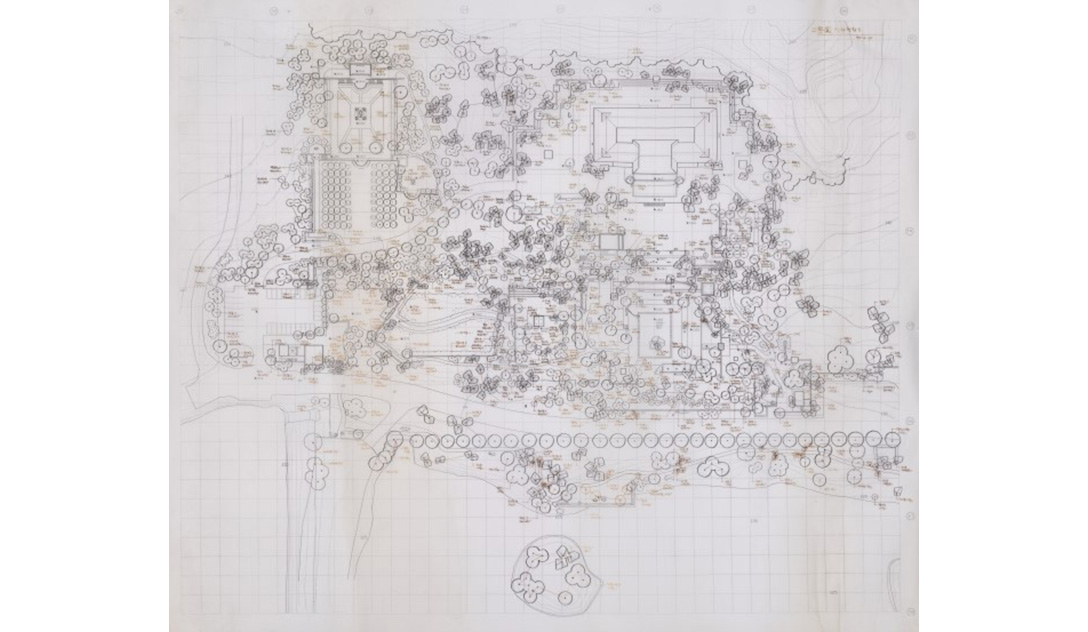

Organized into seven thematic sections, the exhibition’s spatial design is inspired by the traditional Korean ru (樓)—elevated wooden pavilions that frame the surrounding landscape. Visitors move from room to room, experiencing the landscape architect’s gaze as though climbing a pavilion to observe layered scenery. More than 300 archival items are on display, including plans, sketches, models, photographs, and videos. Featured contributors include photographers Kim Yongkwan, Yang Haenam, Shin Kyungsub, and Jung Jihyun, alongside video works by Giraffe Pictures (Jung Dawoon and Kim Jongsin), thoughtfully integrated into the exhibition environment.

Curator Lee Ji-hye noted, “We divided the seven themes in response to the Renaissance building’s layered spatial character and visualized the chronology of Korean landscape history through a 32-meter-long archive installation. The exhibition also echoes the city’s aqueous character and site specificity.”

Interactive programs accompany the exhibition, offering visitors a direct way to engage with Jung’s design philosophy. In Gardening Time, Living Names, and Time of the Mind, Time of Nature, participants are invited to design gardens, explore native Korean flora, and imagine their own contemplative landscapes—encouraging embodied participation rather than passive viewing.

Speaking at the opening, Jung emphasized that “the essence of Korean landscape is beauty that is humble yet never shabby, splendid yet never gaudy,” adding that “design must now embrace the earth with care for future generations.” Architect Cho Min-suk reflected on his long collaboration with Jung, stating, “Working with her taught me how to think and behave as an architect.”

This exhibition underscores landscape as more than technical planning—it reveals landscape as a language that designs the logic of nature and the rhythm of life. It is an act of reading the land, preserving memory, and shaping urban flow. In Venice, Jung’s practice emerges as a multilayered platform where Korean landscape imagination encounters the evolving dialogue of global public space. Photos courtesy of Enrico Fiorese (San Marco Art Centre), Kim Yongkwan and Jeon Jinhong (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art)

Exhibition Themes

1. A Shift in Paradigm: Writing a Sustainable History

This section highlights landscape projects that recover historical memory and site-specific identity. The redevelopment of Gwanghwamun Square (2009) articulates the aesthetics of emptiness while reinterpreting symbolic narratives in a contemporary urban context. The Gyeongchun Line Forest Trail (2015–2017) transforms remnants of a colonial-era railway into a forward-looking public space, exemplifying how landscape can reframe the past into a place of collective future.

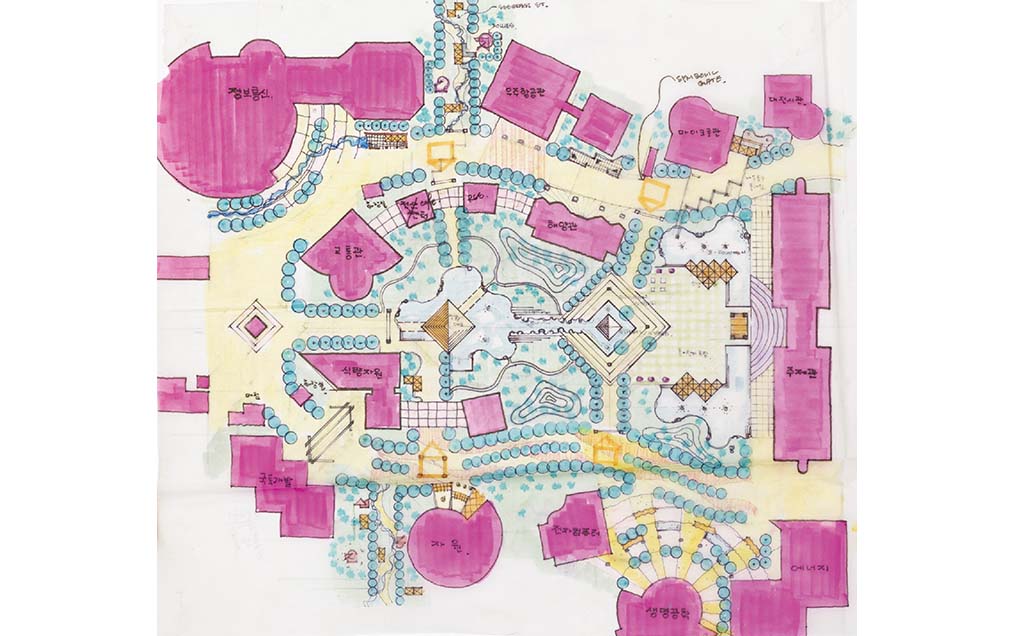

2. Globalization and the Urban Landscape of Korea

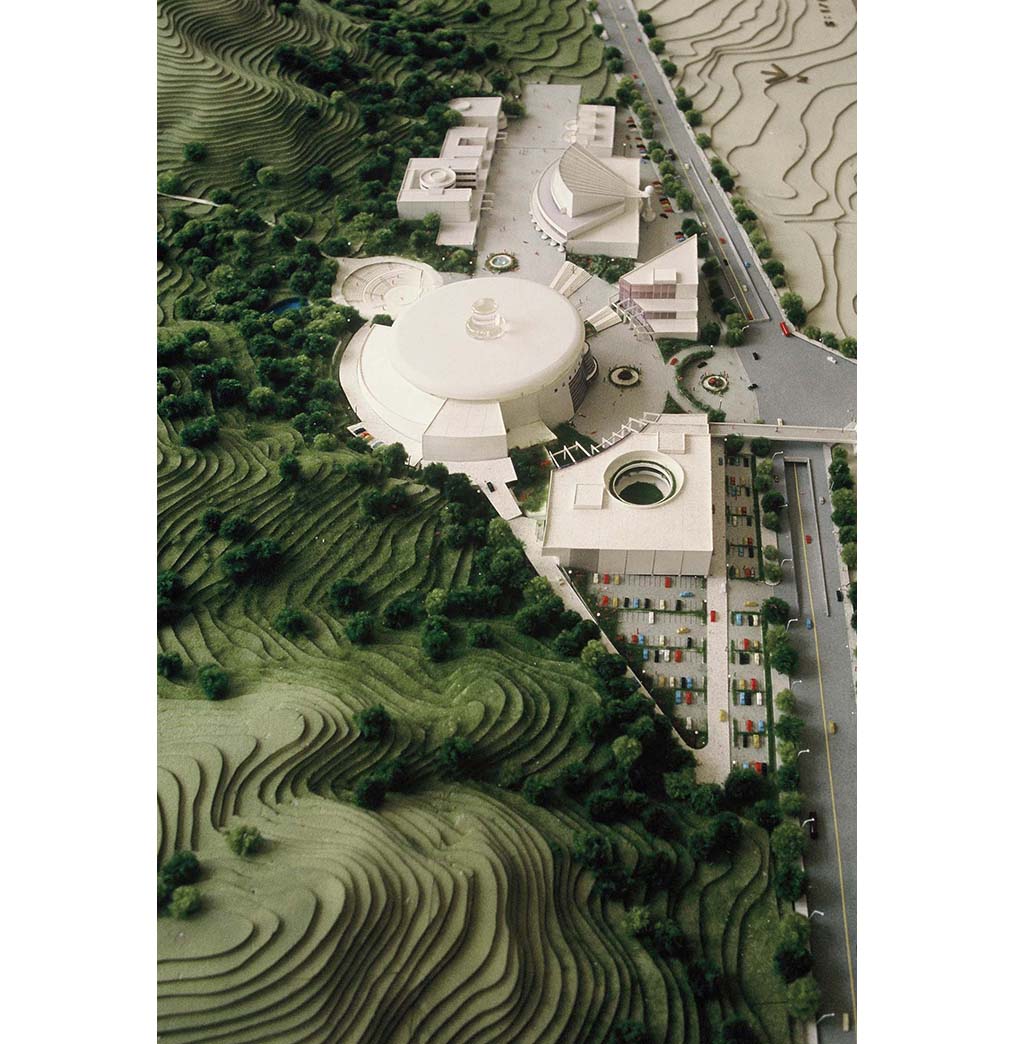

Large-scale national projects like the Daejeon Expo (1993), Asian Games Athletes’ Village (1986), and Olympic Apartment Complex (1988) contributed to shaping Korea’s modern urban identity for an international audience. At the same time, these projects introduced green infrastructure into dense cities, demonstrating how landscape connects ecological systems with civic ambition.

3. Nature, Art, and the Leisure Imagination

Spaces such as the Seoul Arts Center (1988), Phoenix Park (1995), and the upcoming humanities residency Dunaewon (expected 2026) merge art, leisure, and topographic context. Inspired by Heidegger’s Holzwege (Forest Paths), Dunaewon presents landscape not as layout but as a journey of thought—where terrain becomes philosophy.

4. Plants: The Soil of Life

Projects like Asan Medical Center Garden (2007) and Won Dharma Center (2011) reveal the emotional and therapeutic dimension of landscape design. At the Won Dharma Center in upstate New York, native vegetation and expansive grounds converge to form a meditative continuum between architecture and nature.

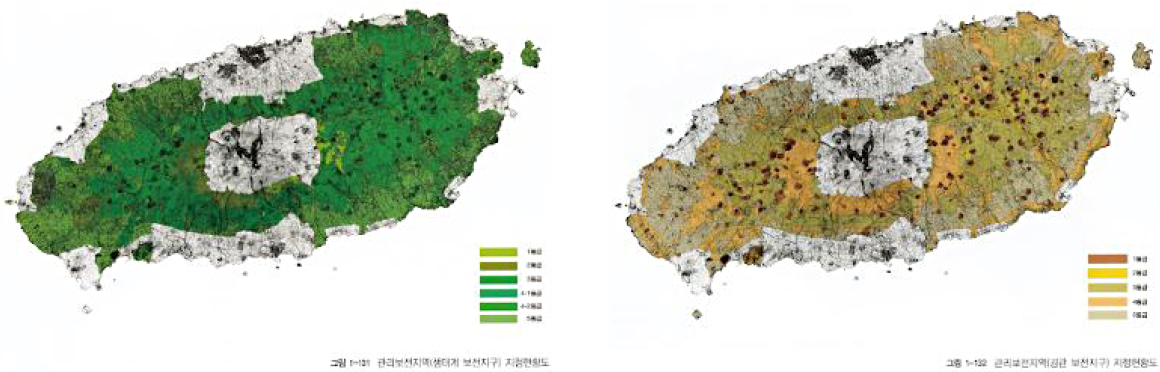

5. River Landscapes and Ecological Recovery

This section showcases the role of landscape in restoring urban ecosystems. Seonyudo Park (2001) and Yeouido Saetgang Ecological Park (1997, 2008) repurpose former infrastructural sites into living ecological corridors—turning the concrete city into a space where time and life flow again.

6. The Reimagining of Korean Gardens

Projects like Heewon (1997), Byeolseo Garden in Pohang (2008), and Haedong Gyeonggi Garden (2005) reinterpret the traditional aesthetics of Korean gardens. Through site-sensitive planting and the principle of borrowed scenery (chagyeong), they revive the native grammar of landscape as gradual visual unfolding and spatial introspection.

7. Dialogue Between Architecture and Landscape

In projects such as Osulloc Tea Museum (2012, 2019, 2023), Moheon (2011), and Southcape Namhae (2013), landscape design becomes the leading voice—not a supporting element to architecture. Collaborations with architects like Cho Minsuk (Mass Studies), Cho Byoungsoo (BCHO Architects), and Seung H-Sang (IROJE) blur disciplinary boundaries, proposing a new sensory language and spatial rhythm.