Throughout cities worldwide, architectural gifts take many forms: libraries funded by wealthy philanthropists, shelters built by humanitarian organizations, farms established with development grants, mosques financed by Islamic foundations, and stadiums gifted as part of diplomatic initiatives. These humanitarian, developmental, and diplomatic contributions are particularly prevalent in rapidly developing metropolises across Africa, Asia, and South America. As welfare states in North America and Europe retract, philanthrocapitalists are increasingly stepping in to fill the gaps, investing in cultural, social, and educational facilities.

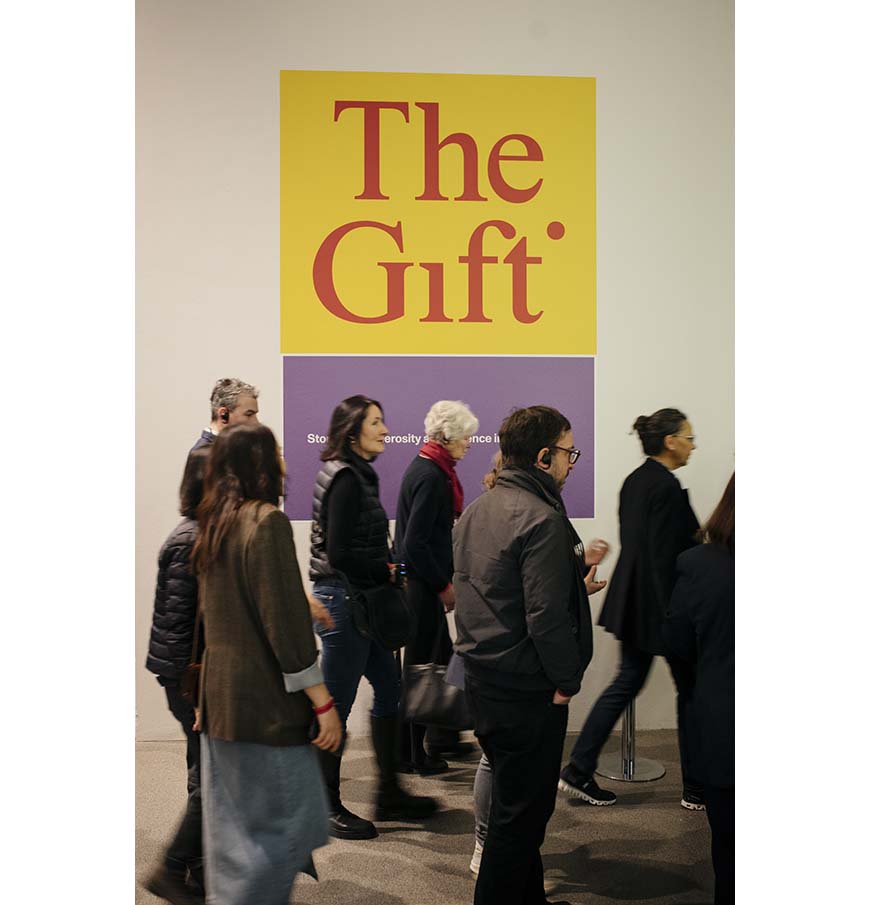

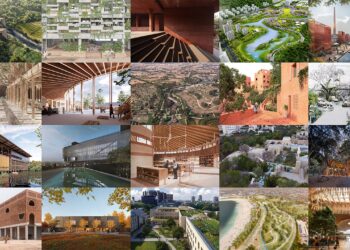

The exhibition ‘The Gift’ is currently on display at the Architekturmuseum in Munich and will conclude on September 8. This exhibition showcases a wide range of gifted buildings—from grand to everyday—and explores how the unequal relationship between donors and recipients can result in both generosity and harm. It explores critical questions: What are the benefits of an architectural gift, and how might it also cause harm? Does such a gift imply an expectation of reciprocity, and if so, in what form? The exhibition further delves into the lasting obligations of both donors and recipients, and how local communities come to perceive and use these structures over time.

To delve into these themes, the exhibition presents four narratives from four continents. The first focuses on Skopje, the capital of North Macedonia, which was rebuilt after a devastating earthquake in 1963. This story highlights donations from across the globe, transcending the geographical and political divisions of the Cold War era, with contributions from African and Asian countries. The second story takes place in Kumasi in the Ashanti region of Ghana, where the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology was established during the late colonial period. The land for the university was donated by the Asante king on behalf of the local communities, who continue to receive reciprocal benefits such as housing and social infrastructure.

The third narrative focuses on housing estates in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, built as gifts from the Soviet Union and China during the Cold War. A Mongolian worker’s apartment, initially provided during the socialist era, remains in use by his children and grandchildren, demonstrating how these gifts have served multiple generations. The fourth story addresses East Palo Alto, California, where a marginalized community has struggled to capitalize on the prosperous opportunities of Silicon Valley. This section explores how residents and authorities navigate the opportunities and risks of architectural gifts from powerful neighbors, such as Meta (formerly Facebook).

As part of this exhibition, visitors are offered a city guide to explore gifted buildings throughout Munich. Outside the museum, a ‘Gift Bar’ made of small furniture pieces has been set up, where discussions on gifting can take place. Additionally, a variety of small events, such as book exchanges, performances, and open kitchens, will be held to delve deeper into the ritualistic aspects of gifting and the power dynamics inherent within them.

The exhibition concludes by returning to Germany, exploring how philanthropy continues to influence cities like Munich. As part of the experience, visitors can explore gifted buildings throughout Munich with a specially curated city guide. Outside the museum, a “Gift Bar” constructed from small furniture pieces offers a space for discussions on gifting. Additionally, a series of small events—including book exchanges, performances, and open kitchens—will explore the ritualistic aspects of gifting and the inherent power dynamics within these acts.