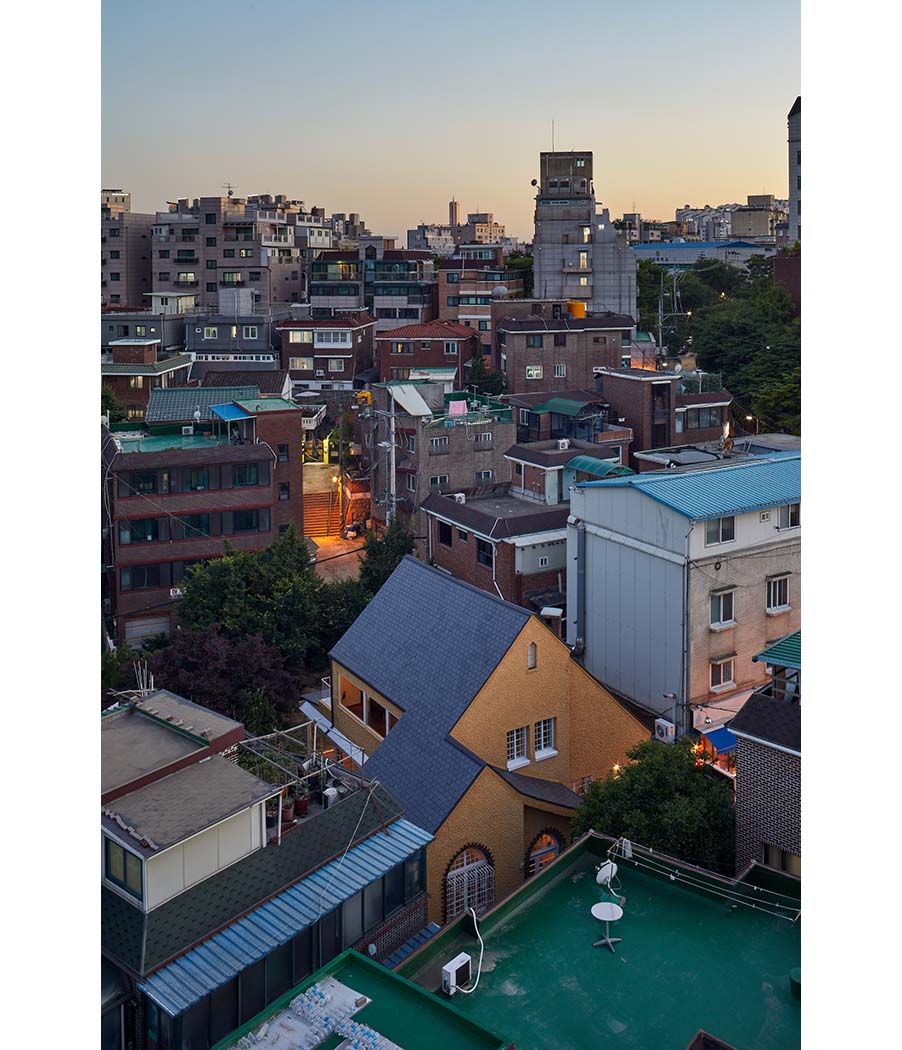

Minimal Intervention in ninety years of memory

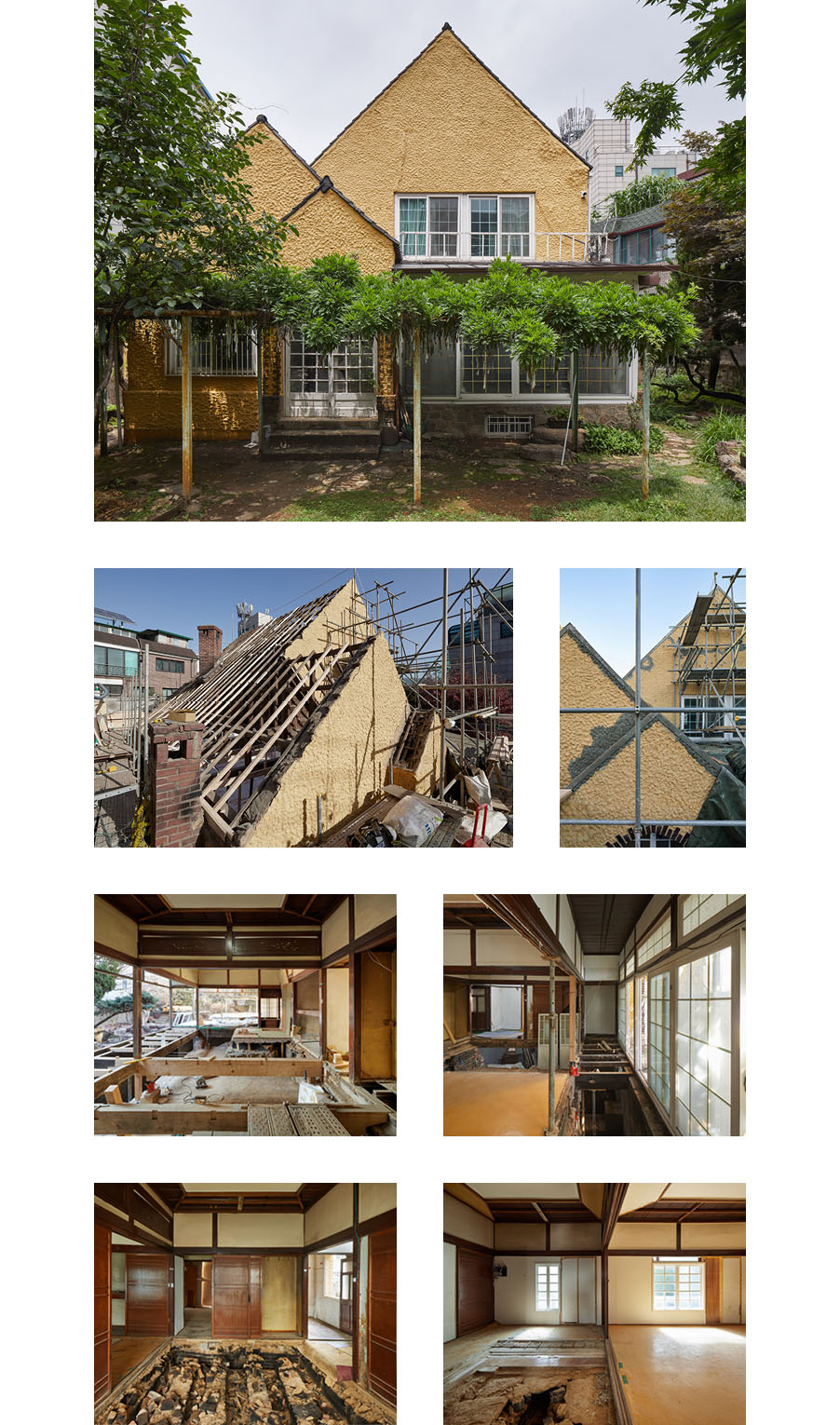

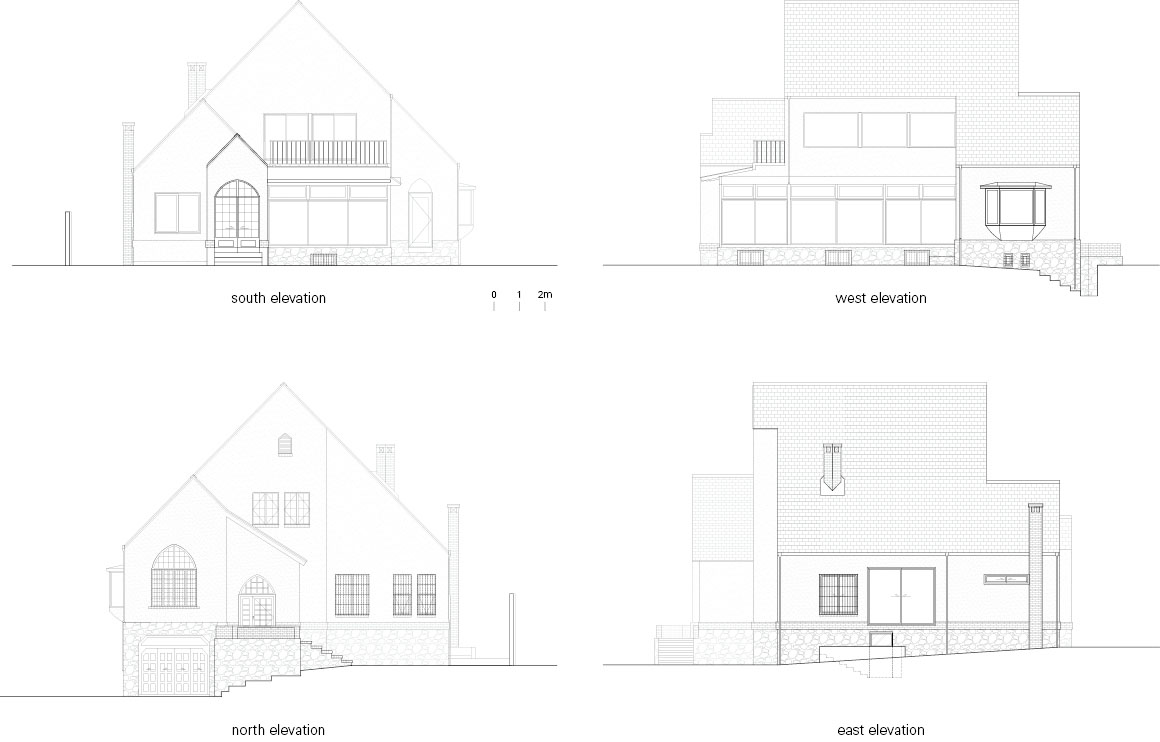

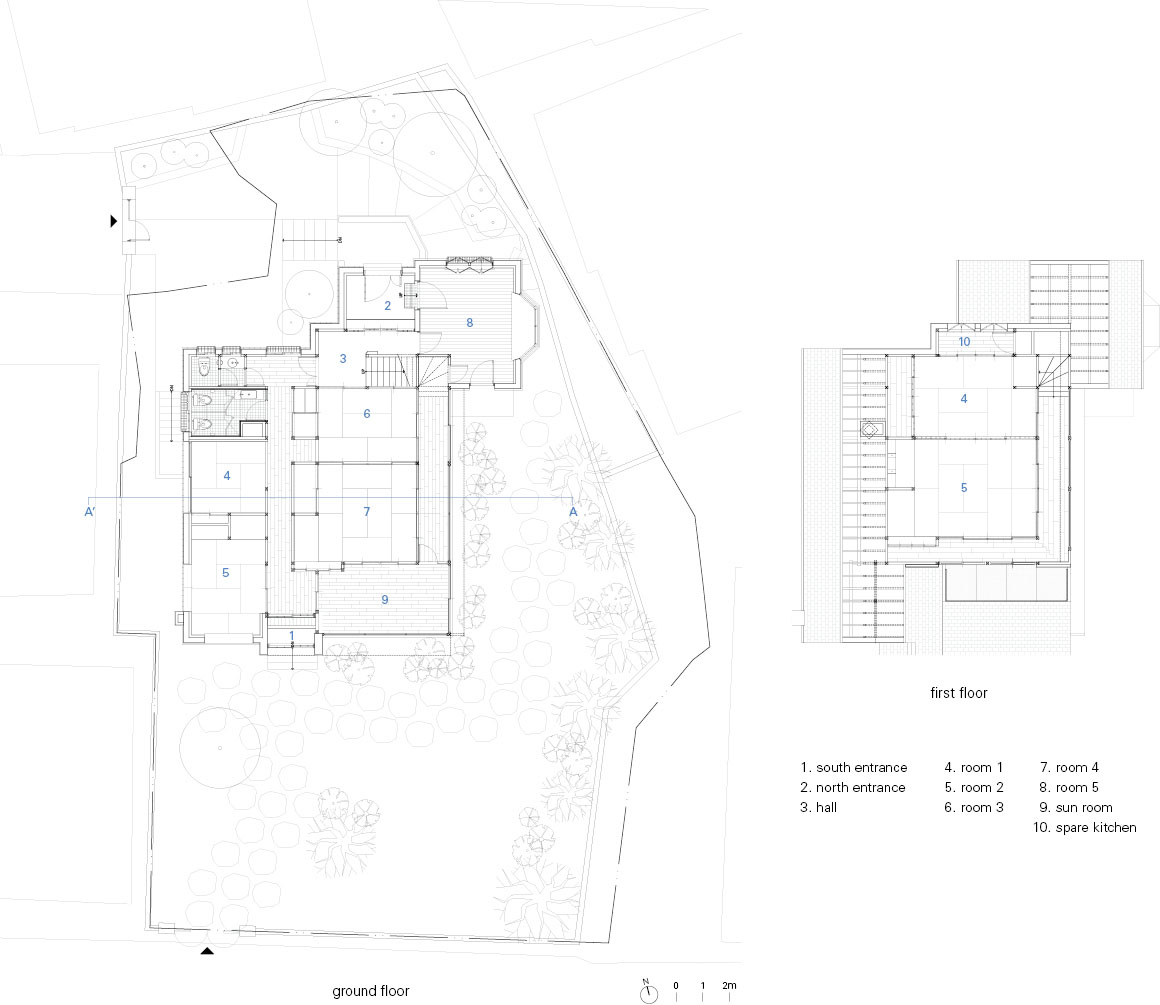

At the end of a sloping alley in Cheongpa-dong, Seoul, stands a house bearing 90 years of history. This residence, built in the 1930s by Japanese architects on the Korean Peninsula, exemplifies the Japanese-Western Eclecticism—a fusion of Japanese traditional wooden construction and Western-style reception rooms. However, this house transcends a mere hybridization of styles. Uniquely, it incorporates Korea’s traditional heated floor system, the gudeulbang, tailored to the local climate and lifestyle.

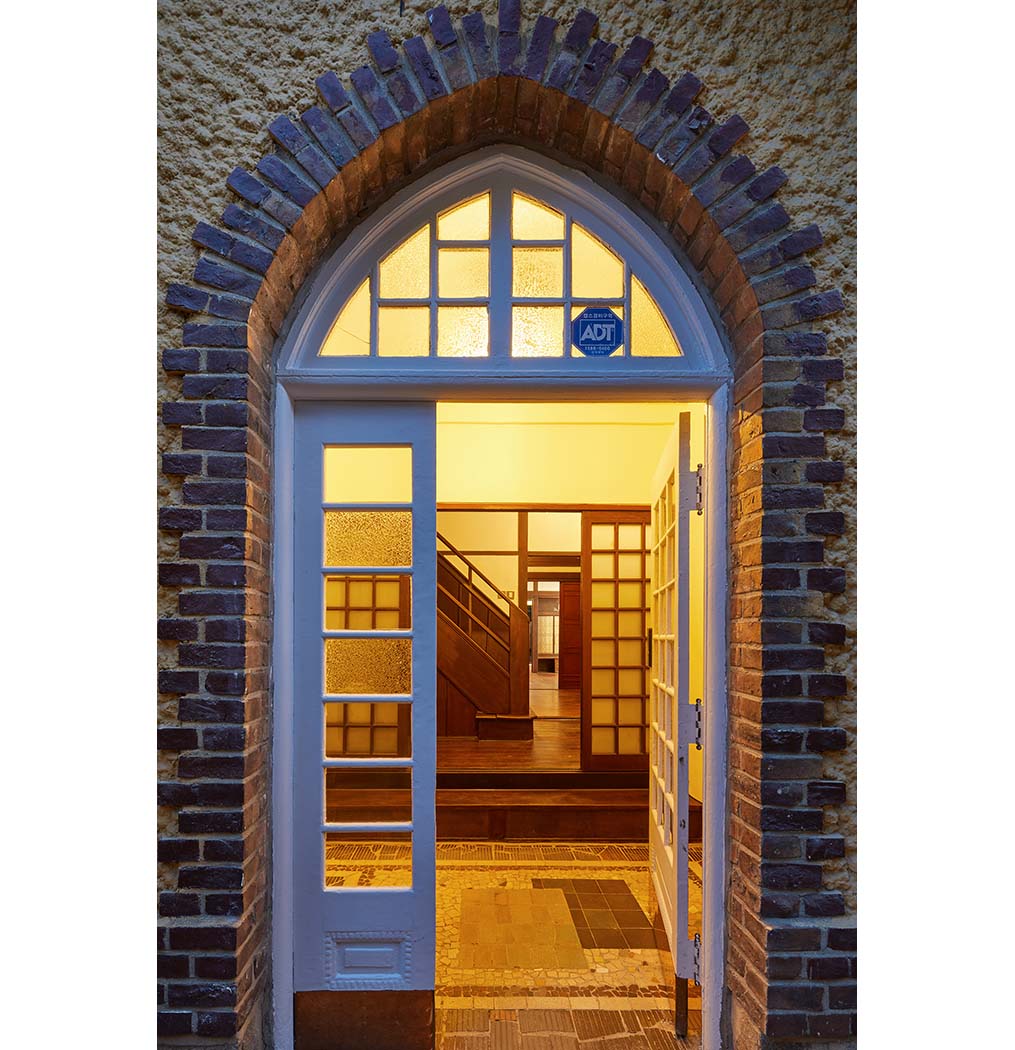

Originally built by Yamazaki Katsusaburo, the Seoul branch manager of the Japanese construction firm Horiuchi-gumi, the house was later classified as enemy propertyJeoksan during the U.S. military administration following Korea’s liberation. In the 1960s, it was purchased by the current owner‘s father, whose family has since resided there. Over the decades, the family has maintained the house, transforming it into both a repository of memory and a living testament to Korea’s architectural and residential history. The owners did not want the house to undergo drastic alteration nor remain in a state of inconvenient preservation. Their goal was to respect the original structure and atmosphere while ensuring the house’s sustainable use in a new era. The architects approached the project with a principle of ‘minimal intervention based on memory,’ taking the house’s history as a design guide.

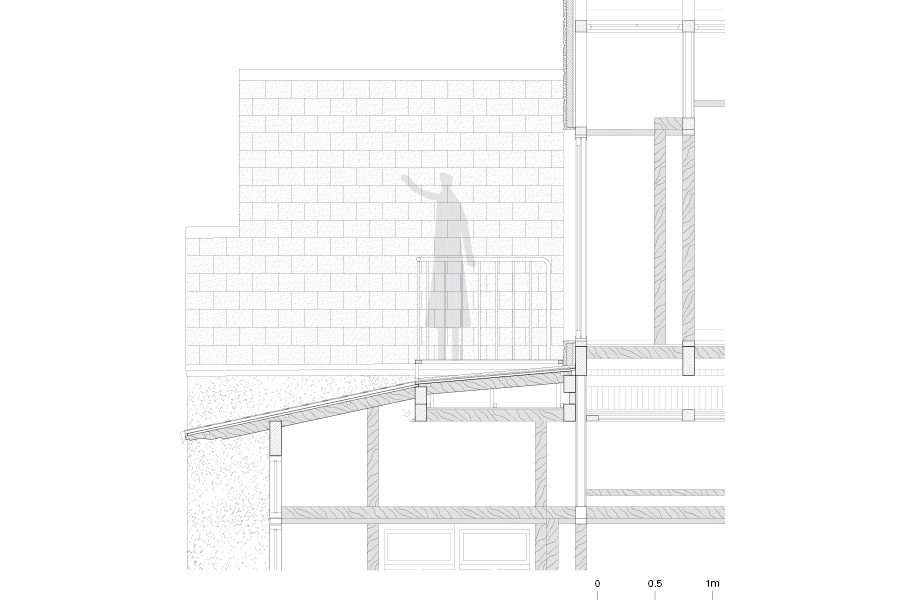

The first step was structural reinforcement. Over time, changes such as the removal of tatami mats and the installation of coal-heated gudeul floors had weakened the original wooden beams, with some replaced by brick columns, leading to structural subsidence. To address this, every column on the first and second floors was measured and realigned to the original height before reinforcement. Damaged wood was replaced where necessary, and inaccessible areas were reinforced with metal plates. The restoration of the interior and exterior walls followed the unique sectional structure of the house, carefully considering the characteristics of each material layer. The walls, composed of a complex mix including lime plaster, sanded walls, earthen plaster, straw, animal hair-infused lime putty, and wire mesh, were selectively dismantled only in damaged areas and reconstructed using the original methods.

The Interior woodwork was refinished with lacquer to revive its original appearance, supplemented by cashew lacquer where needed. Iconic features such as the tokonoma alcove, a hallmark of Japanese houses, were meticulously restored.

Fifteen layers of materials were discovered under the floors, a physical record of changing lifestyles—from tatami to coal-heated gudeul floors, and later copper-piped oil heating systems. Some of these changes were documented on the walls, while the floors were refinished with new wood inspired by the original tatami room layout.

The northern reception room was restored with most of its original materials, while the southern terrace underwent a partial rebuild, retaining only key components. Issues such as termite damage, leaks, and load-bearing deficiencies were resolved while preserving the essence of the wooden structure and its ornamental elements. Original hardware, such as window lattices, 2mm glass panes, door handles, and locks, were repaired and reused wherever possible. Missing pieces were reproduced in forms similar to the originals, adapted to current conditions.

To enhance energy efficiency, window frames were modified to improve insulation while maintaining the original façade. Insulation was also added to the roof, ceilings, and between floors to improve thermal and acoustic performance.

This remodeling was neither a regression to the past nor a complete reinvention. It is a restoration that respects the traces of memory and time, executed with cautious and deliberate intervention. The architect prioritized the natural evolution of the house over imposing their vision. This approach aligns with the architect’s long-standing exploration of ‘remainderness’—the practice of harmonizing with what remains rather than erasing it.

The 90-year-old house in Cheongpa-dong stands as a testament to this philosophy, embodying one way for architecture to coexist with the passage of time.

Project: Cheongpa-dong 90-year-old House / Location: 9-6, Cheongpa-ro 47ga-gil, Yongsan-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea / Architect: Isak Chung (Dongyang University) + a.co.lab (Jinpyo Hong) / Design team: Cho Juhee, Kim Minji, Choi Eunjung, Han Suji, Jin Chaerin, Sung Sejong / Use: Single house / Site area: 541.80m² / Bldg. area: 129.88m² / Gross floor area: 269.42m² / Bldg. coverage ratio: 23.97% / Gross floor ratio: 33.90% / Bldg. scale: one story below ground, two stories above ground / Height: 8.40m / Structure: wood structure / Exterior finishing: cement + paint, stone slate roof / Interior finishing: white cement + general cement + straw / Design: 2018.6~2018.9 / Construction: 2018.6~2019.5 / Completion: 2019 / Photograph: ©Kyung Roh (courtesy of the architect)